The frontier of liberation: how the Russians put an end to the yoke of the Horde

On November 11, 1480, the troops of Khan Akhmat of the Great Horde retreated from their positions on the Ugra River and from the borders of the Grand Duchy of Moscow. This event marked the end of the Horde's yoke, which lasted for more than 250 years for the Russian principalities. Izvestia recalled how it was.

Under the Horde oppression

The Russian principalities had been vassalage to the Golden Horde since the 1240s, since the formation of this state, which became a stronghold and key outpost of the nomadic Mongol Empire in Eastern Europe. After two campaigns by Genghis Khan's grandson Batu against Russia, the exhausted principalities could not resist the invaders. The "Basurman yoke" or "bondage" was established over the ancient Russian state. Such terms are found in the annals.

The Khans of the Golden Horde in Russia were called tsars.: they were considered legitimate authorities. Every year, a "way out" was introduced into the Horde — a tribute, a ten percent "income tax". There were other payments besides him. Stone construction almost stopped in Russia for several decades. The development of crafts and military affairs has slowed down.

Russian princes were supposed to receive labels for reigning in the Golden Horde. The rulers of the Horde acted according to the classic principle of "divide and rule", preventing increased centralization in the conquered lands.

Relatives of the Russian princes — Rurikovich served in the khan's guard. They often became hostages of the Horde. The Horde officials, the Basques, played a major role in the administration of the Russian principalities. Russian squads participated in the military campaigns of the Horde. Sometimes this duty could be bought off.

Note the relative religious tolerance of the Horde. Even after converting to Islam, the khans did not try to convert the "Russian vassals" to their faith. They had enough of military-political dependence and regular payments. They did not impose their culture and lifestyle on the Russian principalities. Moreover, they borrowed a lot from the conquered Rus. Another thing is that in the conditions of the ruin of the Russian land, the development of the economy and culture slowed down.

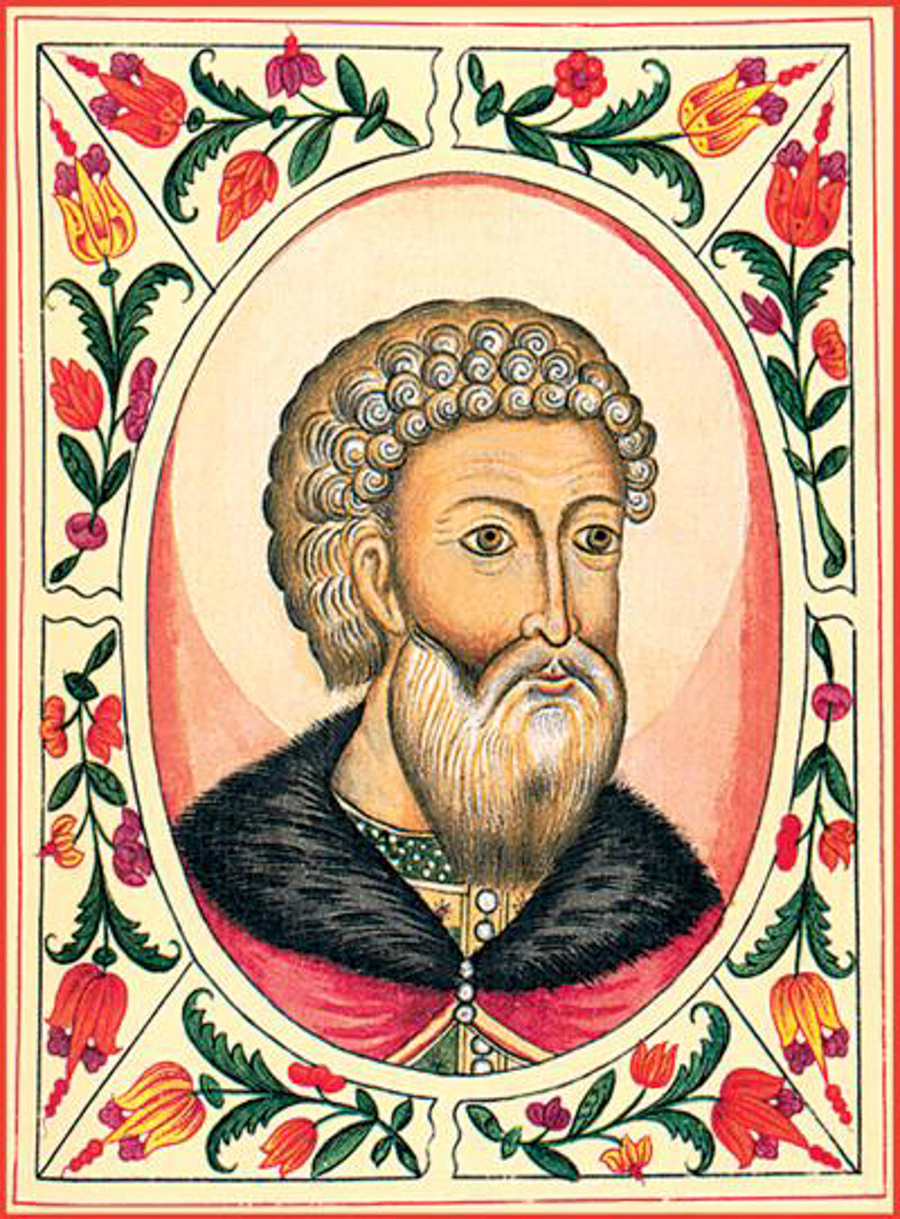

The Age of Ivan the Great

"Present—day Russia was formed by John," wrote Nikolai Karamzin. His contemporaries nicknamed him Ivan the Great. He was born in a time of turmoil and unrest. His father, Grand Duke Vasily II of Moscow, nicknamed the Dark One, fought a protracted internecine war with his cousin Dmitry Shemyaka. The prince was captured and blinded.

In 1448, eight-year-old Ivan became the co-ruler of his blind father. Ivan acted prudently, cautiously, but with an iron will. In the 1470s, he, alternating carrot and stick in relations with his neighbors, subjugated the vast and rich Novgorod lands to Moscow. The principality of Ivan III turned into a truly great one. No wonder, by the end of his reign, his title sounded like this: "By the grace of God, the sovereign of all Russia and the Grand Duke of Volodimersk, and Moscow, and Novgorod, and Pskov, and Tver, and Yugorsky, and Vyatka, and Perm, and Bulgarian, and others." It sounded proud. This development did not suit the Horde at all.

The Strange War

Khan Akhmat issued a label to the Novgorod lands to the Polish king and Grand Duke of Lithuania Casimir IV, who could become a profitable ally for the Mongols. But the ruler of the Horde overestimated his strength. The Grand Duke of Moscow, without interrupting respectful relations with the Khan, pursued an independent, independent policy. The Mongols could put an end to this in only one proven way: to inflict a military defeat on the "Uruses", ruin Moscow, and demonstrate their superiority.

Akhmat summoned Ivan Vasilyevich to the Horde. The khans had not applied to this humiliating procedure for the Russian princes for about a hundred years. When Ivan Vasilyevich refused, Akhmat began to prepare for a punitive campaign against Russia, enlisting the support of Casimir IV.

The situation in Moscow was dramatic that year. In January 1480, Ivan III was opposed by his brothers Boris Volotsky and Andrei Bolshoy, who accused the Grand Duke of infringing on their appanage rights. Ivan III managed to quickly pacify the uprising, the brothers retreated, but did not lay down their weapons. Ivan was preparing for a decisive battle with the rebels. In the struggle for power, he, as befitted a ruler in those days, knew no mercy. In the summer of 1480, Khan Akhmat and his army headed for the borders of Russia. In early October 1480, Russian and Horde troops found themselves opposite each other on two banks of a tributary of the Oka River, the small Ugra River, near Kaluga. They exchanged fire, but both troops were afraid to take decisive action. Chroniclers have found a very accurate word to describe this strange war — standing. Akhmat never got help from the Polish king. Why? Moscow's ally, the Crimean Khan Mengli I Giray, helped. He attacked the southern borders of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and distracted the troops of Casimir IV.

Russian soldiers managed to repel the Horde's attempt to force the Ugra River near the town of Opakov. There, the Moscow soldiers used artillery for the first time, stopping the enemies with "firearms".

The boyars in the majority spoke in favor of resistance: "to stand firmly for Orthodox Christianity against non-Christianity." The soldiers were greatly supported by the confessor of the Grand Duke, Archbishop Vassian of Rostov. At the most dramatic moment of the confrontation, he wrote a "Message to the Ugra," in which he encouraged the soldiers: "And put the warriors under my command, will I, the old one, hide my face from the Tatars?" Perhaps these words convinced Ivan III that fleeing to a safe land would have a bad effect on his reputation. The Grand Duke set out from Moscow and, having received news of Akhmat's unsuccessful attempts to cross the Ugra, set up headquarters in the small fortress of Kremenets. He was still waiting. It was as if he understood that Khan would falter, would not be able to withstand this struggle of nerves.

Ivan III commissioned Prince Vasily Nozdrovaty-Zvenigorodsky, together with Moscow's ally, Prince Nur-Devlet of Crimea, to march to the rear of the Golden Horde. The Russian-Tatar detachment descended down the Volga without encountering serious resistance: the military forces of the Great Horde were involved in Akhmat's campaign. The raid on the Horde capital of Novy Sarai was irresistible and devastating. Of course, this raid affected Akhmat's mood. The Khan lost confidence in his power.

The cold weather set in. It would have been easier for the Horde to cross the Ugra on the ice. The Grand Duke was gathering forces to give them a battle near Borovsk, blocking the way to Moscow. But on November 11, Khan Akhmat decided to move back to the Horde. In Russia, many perceived this as a miracle, they talked about the intercession of the Virgin Mary, who saved Russia. There are other reasons: the noble Horde offered Akhmat to abandon the war with Moscow, complaining about the duplicity of the Lithuanians. And most importantly, both the khan and his military leaders were convinced that Ivan III had a combat—ready, well-armed army and could act simultaneously on several fronts, striking at the Horde.

"He created the current Russia"

A few months after the unsuccessful campaign against Russia, Khan Akhmat died. The Great Horde split into several uluses. Since that time, there has been no need to talk about foreign hegemony on Russian soil. Moscow learned to conduct politics on its own and soon extended its influence to the "fragments of the Horde" — primarily to the neighboring Kazan Khanate. In 1497, Ivan III issued a Judicial Code, the first unified collection of laws in Moscow Russia.

Standing on the Eel has remained in history as an example of a bloodless victory over a long-time most dangerous enemy. The neighbors were convinced of the strength of the Russian army and the ability of the Grand Duke to conduct an independent and firm foreign policy. The alliance with the Crimean Khanate proved to be a very effective alliance. Perhaps for the first time in the history of our country, the two powers acted in concert and successfully, despite their geographical remoteness. The diplomatic talent of the Grand Duke, who was able to negotiate, was able to firmly pursue the common interests of the allied states, had an effect. He understood, despite the inevitable medieval prejudices at that time, the importance of international cooperation and supported the boyars, who showed talent as a negotiator.

The consequences of standing on the Eel and the politics that preceded this victory are astounding. At the beginning of the reign of Ivan the Great, the Muscovite state, firstly, remained dependent on the khans, and secondly, it was squeezed between the Horde and Lithuania. After 1480, the neighbors began to treat the Russian state much more seriously than before. For many, Moscow's rise came as a surprise. Karl Marx reasoned about it many years later: "Astonished Europe was stunned by the sudden appearance of a huge empire on its eastern borders, Sultan Bayezid himself, before whom it trembled, heard for the first time arrogant speeches from Muscovites."

Ivan III, according to the exact definition of Nikolai Karamzin, left behind "a state amazing in space, strong in peoples, and even stronger in the spirit of government... He created the current Russia." And independence was gained in late autumn, on the foggy shores of the Ugra.

The author is the deputy editor—in-chief of the magazine "Historian"

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»