Fate and man: Izvestia publishes a fragment of the Kazakh family saga

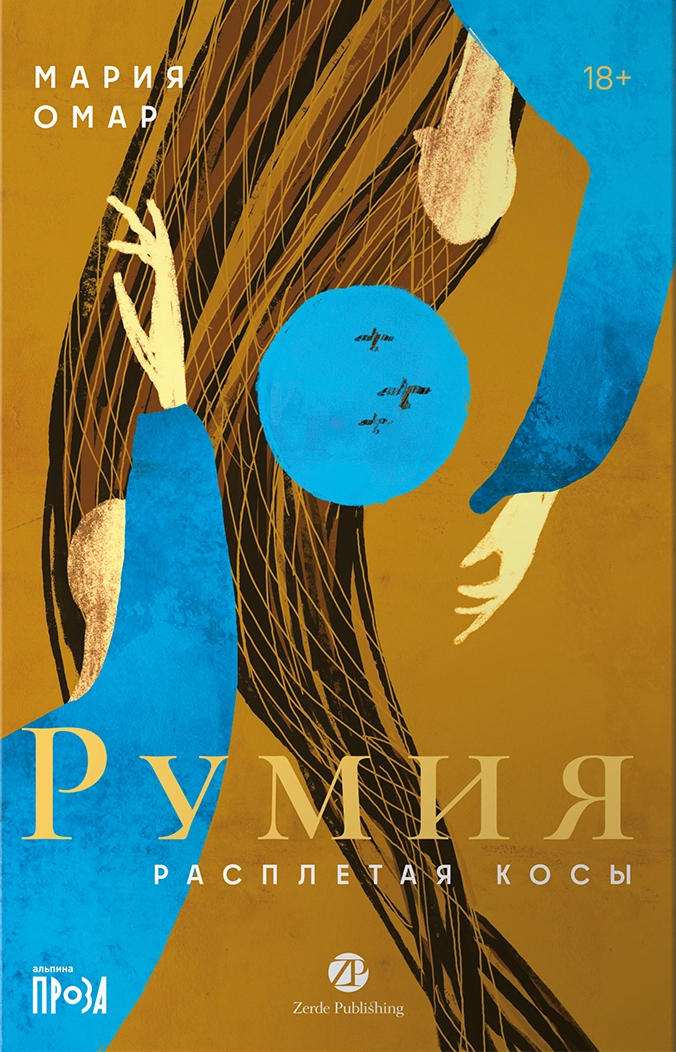

The name of the Russian-Kazakh writer Maria Omar became known in 2020, after the release of her debut novel "Honey and a little Wormwood", in which she tells about the life of her grandmother, who left her native steppe in the hungry post-war years and went into the unknown with two children. The genre of the new book, Rumiya, can also be defined as a family saga, but here the main character is a girl, half Tatar, half Kazakh, and therefore feels like a stranger everywhere. Izvestia publishes a fragment of a work published by Alpina. Prose" on the eve of the book's appearance on store shelves.

Maria Omar "Rumiya" (fragment)

1987, village of P. near Aktobe — Aktobe

Finally, Abika cooked noodles for dinner and went to her room. There's definitely an hour until Mom comes.

Rumiya throws on a sweatshirt, puts blue knitted leggings and spiky wool socks on tights, puts a down shawl on her head, crosses its ends under her neck. On top of everything, my dad's sweatshirt: I don't want to put my coat in the barn, it smells like manure. Felt boots with galoshes are also Dad's, above her knees. The door swings open, almost breaking off in the strong wind; Mom is always grumbling that Dad won't put another, stronger one.

The sharp snow stings my eyes and cheeks. The sun is barely shining in a dim spot. Rumiya falls in front of the barn — the galoshes are slippery. She winces — she's hurt her knee. He lifts the wire ring over the gate, enters the card (cattle pen — author's note), then into a large barn. He accidentally steps on a fresh lump of manure and holds his nose with his fingers. Cow lying down chews cud. Rumiya scratches her warm, soft-creased neck.

There are sheep in the pen. Rumiya enters, slams the light door behind her and catches the lamb. He bleats, pressing himself against the wall, ducking under the sheep. They're yelling too. Rumiya sits on her knees, running her fingers through her tight curls. And why are you shouting? She finds the warm, taut udder of a sheep and brings the lamb to it. He starts sucking, comes off, bleats again.

Rumiya takes a bucket of grain from the bin with her and goes to a small barn. Pigeons fly out of there, almost knocking her down. They're going to bask here.

—Nate, nate," she pours the grain onto the wooden floor.

The pigeons are coming again.

When there are about twenty of them, Rumiya slams the door.

And now to catch! This one is so beautiful, white, with brown spots. White pigeons are the neatest. It's like they know they're different from others. She grabs him in the upper corner of the barn, under the low ceiling. The pigeon, trying to escape, flaps its wings. Rumiya gently presses them against his body.

— Well, well, how stupid, I won't hurt you! On!

He puts a grain in the palm of his hand under his beak. He just rolls his round eyes. Why are pigeons smart in the movies, even drinking from their owner's mouth. And these!..

Abika cursed when she saw Rumiya grabbing pigeons:

"They're wild!" They bring any kind of infection, don't touch it!

Now Rumiya catches them when no one is at home.

— Okay, fly!

The pigeon takes off sharply and hits the ceiling.

Rumiya squeaks through the snow back to the house. Boring. Aika is sick, she hasn't been back for a week. The parents will come tired: "Rumi, leave me alone! My head is spinning without you!"

She sits down at the table, picks up pencils and a new album. Maybe Mom will be cheerful today? For some reason, she's been angry all the time lately. Rumiya heard Abika telling her, "We can't have boys!" Her mother was yelling at her then. It's strange, what kind of boys is this about?

An oval with a pointed chin, thin eyebrows, lips stretched in a wide smile, a long neck with beads, open shoulders and arms, a belt, flounces diagonally on a narrow dress appear on the sheet. Although Mom smiles only with the tips of her lips and doesn't wear it, it would definitely suit her. Above Papa's head, Rumiya draws a light bulb on a wire to make it clear how tall he is. The sharp corners of the shirt collar, the belt on the trousers. Abika is the most difficult to draw: her face is wrinkled, and if you make stripes, it turns out ugly, but she has a beshpet (a kind of doublet, vest — author's note) with patterns. Papa Rumiya's face is usually painted over with carrot color, his skin is the darkest of all. She portrays herself in a full skirt, like a princess. All four of them — Dad, mom, Abika and Rumiya — are cheerful and holding hands.

And they don't need any boys.

— Ah, ma-ma!

Rumiya's voice breaks off, she no longer screams, but howls, screams, moans, wheezes.

Mom grabs her and drags her to the faucet, thrusting her red foot under the cold water.

Rumiya calms down for a while and screams again:

"It hurts!"

— That's why you were climbing? All the milk spilled!

— I wanted to help!

Rumiya sobs, a burning pain seizes her from the little finger on her scalded foot to her heart. She snuggles up to her mom.

"Be patient, daughter! Oh God, what am I going to do?

I want to bite her. How can you tolerate it? Mom's robe is getting wet from Rumiya's tears. She burrows into the milk-scented folds and grabs the fabric with her teeth. Painfully. Painfully.

Everything in the hospital is in dirty colors. The walls were half-painted dark green, the ceiling was gray with brown spots, and the bedside tables were peeling with remnants of blue enamel. Even the sky in the window is cloudy, like the water in a nurse's bucket after mopping the floors.

Rumiya feels dirty too. She's wearing the same dress the ambulance brought her to town in: flannel, homemade. An unwashed head with disheveled pigtails and a burned leg itch. Abika says when it itches, it heals. How will it heal if every time the bandage is changed, the skin is peeled off. The bandage dries to the wound, and the nurse tears it off along with the caked crust.

In the hospital, Rumiya hates mornings. It starts with the light of a lamp shining directly into your eyes and a loud voice.:

— For the procedures!

Rumiya wants to continue lying under the scratchy blanket, but she gets up, puts her feet in flip-flops and trudges into the office with the white open door, which smells bitter.

The nurse cuts the bandage with scissors: shih, shih. He's going to start fighting now. Rumiya clenches her teeth in advance and winces.

— Ouch!

"Don't move! Wow, she's so impatient. You're a big girl! How old are you?"

"Seven."

The nurse throws a bandage with brown spots into a bucket, smears the burn with a bright orange ointment that slightly soothes the pain, and wraps a snow-white bandage tightly around the leg. The nurse talks to Rumiya's sweet roommate in a different way, affectionately, and touches her wounds carefully. Maybe it's because Mila's pigtails are neatly braided and she changes her clothes every day?

Back in the room, Rumiya tries to comb her tangles, passing them between her fingers, but her hair gets even more tangled, and she doesn't have a comb.

After lunch, Mila's mom comes over. She smells delicious of chocolate lipstick, Rumia's mom had one. When the sponge was almost gone and it became difficult to get it, mom picked out the remains with a match wrapped in cotton wool and ran it over her thin lips. Rumiya also sometimes put her finger into her lipstick.

Mila's mom is friendly to everyone. He takes the labeled jars to the buzzing curved refrigerator and asks what to bring next time. Catching Rumiya's gaze, he holds out a large red apple.:

— Here, girl! What's your name? I forget all the time. Rania?

Rumiya is silent.

Mila's mom puts an apple on her bedside table. A nurse enters:

— Are you all right?

Rumiya lies down and closes her eyes.

He hears the whispers of Mila's mother and the nurse:

— Take it.

— Yes, you gave it yesterday!

— You have a hard job, take it.

— Oh, thank you! Is there anything else you need?

—Oh, no, no," he said. And they still don't come to visit this girl from the village? Poor… How can that be?

Rumiya turns away so that they don't see the tears that are about to roll out from under her eyelashes.

"Why don't they come? — she wants to say. Loud and clear, like an adult. — Mom recently brought oranges. And Dad made a big doll. Mila doesn't have one! Abika treated everyone to echpochmaks and plum paste! Your Mila was eating marshmallows like a sweetheart. And my mother is a hundred times more beautiful than you and richer! She'll give the nurse money, and she'll be kind to me too. Do you think I don't know? You're smiling because Mila's mom is paying you!"

So what if no one actually came. Abika is old, she doesn't know how to travel to the city, and Dad and mom have a lot of work. And don't feel sorry for her. Abika always says: but we are honest.

Rumiya bites her lips, remembering how she got burned. That day, when my mother came home from work, the first thing she saw was not her drawing hanging on the whitewashed wall in the hallway, but galoshes stained with manure. She didn't swear, only said in a voice that made Rumiya's stomach ache.:

— When I was your age, I mopped the floors, watered the garden, and tended the calves. You're growing up spoiled and sloppy!

Rumiya imperceptibly removed the drawing from the crooked carnation, crumpled it up and put it in her pocket.

Mom put on warm pants, a stretched house jacket, a washed robe on top, took a clean bucket and went to milk the cow. Half an hour later, she brought fresh milk bubbling like soda, strained it through cheesecloth into a tall saucepan, put it on the gas stove, and sat down to peel potatoes. Then she was shouted from the street, and Mom went to find out what was the matter. Rumiya saw that white foam was rising in the pot, ran over, began to stir the boiling milk with a spoon — it was already pouring over the edge and sizzling. Rumiya grabbed the pot, wanted to move it, but pulled her fingers back. The pan swayed and began to fall. With a squeal, Rumiya jumped back.

Mom in the ambulance said: "It's a good thing that only my legs got burned." I should have just turned off the gas.

Before going to bed, Rumiya smooths out the crumpled drawing and puts it under her pillow. Thoughts, like pigeons pecking at grain, swarm in her head. What if no one comes to pick her up? How would she get home then? And why did Mom stop loving her?

At night, Rumiya wakes up. It felt like a poisonous apple was stuck in my throat. It stings in my chest. She wants to reach for the glass of water on the bedside table. She gasps for air and can't breathe.

—Ap-ap,— he tries to part his lips. They stuck together like in a scary story. The tree in the window is waving its branches, and a squeaky voice is heard:

"You can't do anything!"

— Mom! Rumiya whispers through her tears. "Pick me up, I'll be careful."

The houses have dazzlingly whitewashed walls. Mom and Abika hate dust and mess.

At home, the curtains are bright blue, like watercolor paint.

At home, you can walk with bare feet, without bandaging or peeling off new skin. They say there will still be scars.

There will be no nightmares at home. Everyone's family is here.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»