A writer can offend an artist: a sarcastic Englishman looks at paintings

Russians Russian translation of the original title, Keeping An Eye Open, by Julian Barnes's new book, would be very suitable for the mischievous Russian idiom "Take off your eyes." However, the publishers decided not to take any chances and preferred a decent offer to the reader to open his eyes in order to get acquainted with another batch of snide observations about fine art from a British postmodernist. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week specifically for Izvestia.

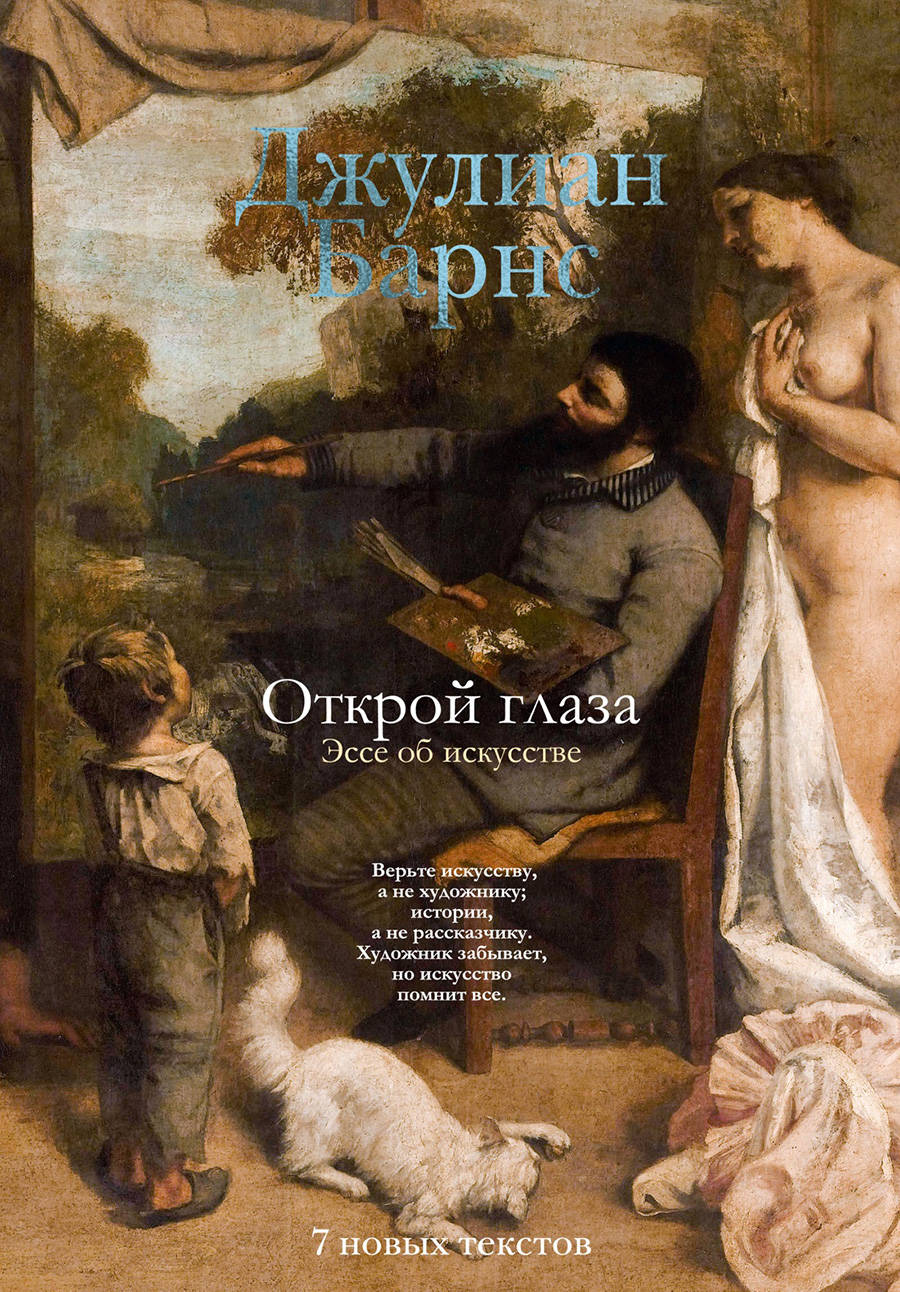

Julian Barnes

"Open your eyes. An essay on art"

St. Petersburg: "ABC", "ABC-Atticus", 2025. — translated from English by V. Akhtyrskaya, V. Babkov, A. Borisenko and others — 416 p.

A collection of essays by Julian Barnes about his perception of painting opens with an old work, which the author obviously values very much, a fictionalized analysis of the painting by Theodore Gericault "The Medusa Raft", first published in the framework of the novel "The History of the World in 10½ chapters" in 1989. This is a pretty spectacular beginning, especially since the tragic prehistory of the painting itself is quite fascinating, and Barnes does not spare the greasiest colors, presenting it in person, reviving each of the characters in the painting, and then smoothly moving on to general theoretical discussions about how to embody the catastrophe in art. Here the writer is seized by bouts of pathos, familiar to all his readers, who are already accustomed to the fact that the most important concepts must be written and pronounced with a capital letter, with additional reverence. "Of course, we must understand it, this catastrophe; and in order to understand it, we must imagine it, hence the need for visual arts. But we also strive to justify and forgive, at least partially. Why was he needed, this crazy twist of Nature, this crazy human moment?" - Barnes reflects, justifying all kinds of disasters and troubles by saying that they become food and soil for brilliant works of art.

Does Barnes' "Medusa's Raft" look any different now, placed in a different context? Perhaps not, except for the fact that the author has aged 35 years and from the height of his life can no longer just pour out the emotions experienced in front of a particular picture, but also build solid conceptual structures. Recalling how he first began studying art history with the creepy painting by Gericault, Barnes systematizes the accumulated experience of a gallery regular.: "I was not guided by any definite plan, but when I put my texts together, I discovered that I was inadvertently following the very plot that I began to unwrap uncertainly back in the 1960s: the history of the art movement (mostly French) from Romanticism to realism and to modernism."

The transformations of pictorial romanticism and its proportions in the work of a particular painter ("If the romantic Delacroix lacked a romantic temperament, then the realist Courbet possessed the egomania of a true romantic") remain the leitmotif of the book, which the author never forgets, seemingly spontaneously and naturally jumping from one artist he likes to another. At the same time, sympathy does not in any way interfere with rather caustic and revealing remarks, for example, regarding Gustave Courbet, whom Barnes attributes as an indisputably great artist, but at the same time a prudent self-promoter: "For all his libertarian socialism, for all his shaking of the foundations and sincere desire to clean up the neglected stables of French art, there was still a lot of Yevtushenkovism in him, a lot from a licensed rebel who knows how far to go and how to monetize his anger."

What Barnes calls "Yevtushenkovism" (a carefully calibrated pose when, at any moment of the most sincere passion, you perfectly control how you look from the outside) is fully inherent in himself, who diligently adheres to the image of a cheerful modernist who breaks dilapidated realistic foundations and is a little jealous of artists with their more flexible tools: "From Of all the arts, music is the most envied by writers, because it is both extremely abstract and at the same time direct, and also does not need translation. However, painting is quite a bit inferior to it, because the expression and means of expression in it coincide in time and space, whereas novelists are doomed to suffer, slowly, consistently, step by step, scrupulously choosing a word, building first a sentence, then a paragraph, inventing a background, giving images psychological credibility in order to create a climactic scene.".

The new collection also perfectly traces Barnes' favorite inner plot, which has long been occupied (or rather, strained) by the theme of aging and the inexorably ending time of life, which is clearly heard, for example, in the essay "Selfie with Sunflowers" dedicated to Van Gogh: "I'm not sure that Van Gogh's paintings have changed a lot for us since It's time that we start to look at him in a different way and discover more about him in our 60s or 70s than we did in our 20s. Rather, it is the artist's desperate honesty, his bold, magnificently bright color, and his deeply sincere desire for "something comforting" in his paintings that bring us back to our youth, allowing us to feel like we are twenty again. And it's not such a bad time. Therefore, perhaps it's really time to take a selfie with "Sunflowers".

In principle, all of Barnes' arguments about artists are a kind of selfie against the background of more or less famous paintings: any character in the book is interesting to the British fiction writer only to the extent that it reflects and helps to highlight writer's complexes, fears and obsessions. But it is precisely this overwhelming subjectivity that makes Barnes's art criticism interesting, when even dubious remarks, bold exaggerations and controversial conclusions evoke purely human sympathy.: This is not the cold analysis of a museum curator trying to figure out the best display of masterpieces, but a touching attempt to see your own pain points in each painting and, if possible, scratch and dig them all the way to the stretcher.

As part of this course of his own psychotherapy, Barnes, at the very beginning of the book, enjoys going through his parents, who had a bad taste in art and therefore all sorts of junk hung on the walls, and at the same time coquettishly informs about his correct sexuality: "Naked oil in a gilded frame was probably an obscure copy of the XIX century with the same an unknown original. My parents bought it at an auction in the London suburb where we lived. I remember her mainly because I found her completely anti-erotic. It was strange, because most of the other images of undressed women had a healthy effect on me, so to speak. It seemed that this was the meaning of art: by its solemnity, it deprives life of joy."

Admittedly, the last remark is not devoid of accuracy and wit: the tradition of talking about great masterpieces with solemn respect often deprives the reader of the joy of reading art history literature. Barnes has been heroically fighting this old tradition all his life and is winning another small victory over it.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»